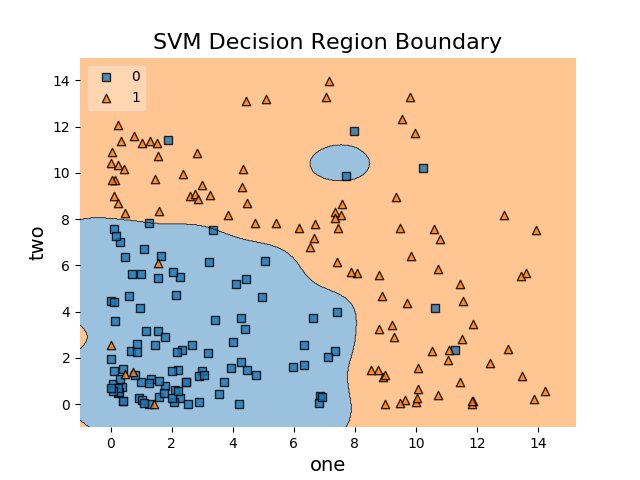

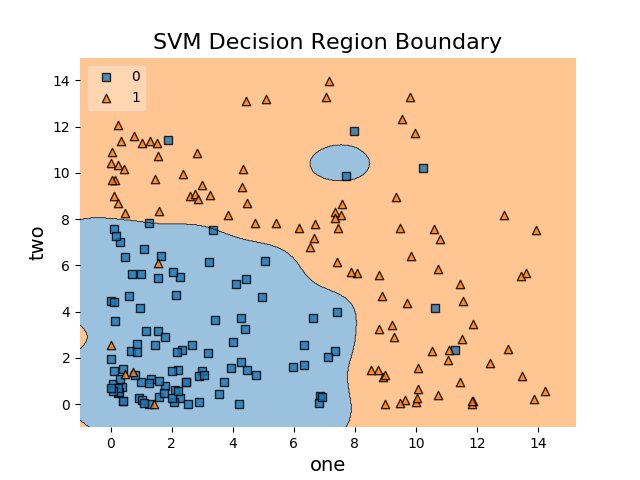

Support Vector Machine is one of the most popular Machine Learning algorithms for classification in data mining. One of the prime advantages of SVM is that it works very good right out of the box. You can take the classifier in it’s generic form, without any explicit modifications, run it directly on your data and get good results. In addition to their low error rate, support vector machines are computationally inexpensive in contrast to other classification algorithms such as the K Nearest Neighbours.

Support Vector Machine algorithm is a supervised learning algorithm, ie. it needs training data. You will have to feed the algorithm training data for it make predictions on the actual data.

In my previous blog post, I had explained the theory behind SVMs and had implemented the algorithm with Python’s scikit learn. If you are not very familiar with the algorithm or its scikit-learn implementation, do check my previous post.

The implementation can be divided into the following:

W and b.I’ve used the classic “Iris” dataset from the UCI ML repository. We will be predicting the type of Iris based on many input parameters. The predict class is binary: “Iris-setosa” or “Iris-versicolor”.

The dataset will be divided into ‘test’ and ‘training’ samples for cross validation. The training set will be used to ‘teach’ the algorithm about the dataset, ie. to build a model. The test set will be used for evaluation of the results.

I’ve modified the original data set and have changed the number of classes to 2. You can find the modified dataset here.

The original dataset has the data description and other related metadata. You can find the original dataset from the UCI ML repo here.

The first thing to do is to read the csv file. To deal with the csv data data, let’s import Pandas first. Pandas is a powerful library that gives Python R like syntax and functioning.

import pandas as pd

Now, loading the data file:

df = pd.read_csv(r".\data\iris.csv") #Reading from the data file

The first thing is to convert the non-numerical data elements into numerical formats. In this dataset, all the non-numerical elements are of Boolean type. This makes it easy to convert them to numbers. I’ve assigned the numbers ‘4’ and ‘2’ to positive and negative Boolean attributes respectively.

df.replace('Iris-setosa', -1, inplace = True)

df.replace('Iris-versicolor', 1, inplace = True)

In main.py:

dataset = df.astype(float).values.tolist()

#Shuffle the dataset

random.shuffle(dataset) #import random for this

Next, we have split the data into test and train. In this case, I will be taking 25% of the dataset as the test set:

#20% of the available data will be used for testing

test_size = 0.2

#The keys of the dict are the classes that the data is classified into

training_set = {-1: [], 1:[]}

test_set = {-1: [], 1: []}

Now, split the data into test and training; insert them into test and training dictionaries:

#Split data into training and test for cross validation

training_data = dataset[:-int(test_size \* len(dataset))]

test_data = dataset[-int(test_size \* len(dataset)):]

#Insert data into the training set

for record in training_data:

#Append the list in the dict will all the elements of the record except the class

training_set[record[-1]].append(record[:-1])

#Insert data into the test set

for record in test_data:

# Append the list in the dict will all the elements of the record except the class

test_set[record[-1]].append(record[:-1])

Before we move forward, let’s create a class for the algorithm.

class CustomSVM:

def __init__(self):

pass

We have the CustomSVM, that will be our main class for the algorithm. In the constructor, we do not have to initialize any value.

Now, let’s define the functions that go inside the CustomSVM class. For the simplicity of this tutorial, we will not delve into Advanced SVM topics such as kernels. For our simple implementation, we will only need two functions - fit and predict.

As their names suggest, the fit function will use the incoming data to model a SVM - essentially calculating the values for W (feature vector) and b (bias). If you are unfamiliar with the terminology or the theoretical fundamentals of SVMs, you can read about it here. The predict function will predict the classification for the incoming parameters, deriving it from the model we ‘fit’ from the training dataset.

First we have the fit function. We only need the pre-processed data set as a param for fit, that’s all we need to model a SVM at this point.

def fit(self, dataset):

pass

Let’s define the predict function. The predict function take in the attributes, ie. the incoming values for which we need to make a prediction. The predict function will use the model that will by created by the fit function

def predict(self, attrs):

pass

Let’s define the test function. The test function takes in the a list of attributes, ie. the test data set for our cross validate. The test function will use the model that will by created by the fit function and use predict to predict the classes of test data. We will calculate the accuracy of the algorithm.

def test(self, attrs):

pass

fit function:The fit function is the core function of our implementation. This is where we will train algorithm based on the training data set provided. This function will model the data by calculating values for W - feature vector and b - bias. In the fit function, we will be be trying to find the optimal values for W and b, essentially trying to approximate the solution for the equation: WT x + b = y. The predict function will use the calculated values of W and b to find the classification for any new input data points based on the input data point x. The fit part of the algorithm is where do our optimization. In SVMs, we are to perform convex optimizations.

A convex optimization problem is a problem where all of the constraints are convex functions, and the objective is a convex function if minimizing

In this tutorial, we are not going to delve into the depths of optimization problems and the theoretical aspects behind them. If you are interested in exploring convex optimizations further, here is a good resource for you to do so. You can also refer here if you want know more about the optimization problems and the geometry behind them.

Let’s get started out on our SMO optimization.

For our implementation, we are going to optimize using the SMO (Sequential minimal optimization) method. SMO is one of the older optimizations used in SVMs and are relatively easier to implement. Needless to say, there are much more complex and better performing optimizations out there. The Sequential Minimal Optimization (SMO) algorithm is derived by taking the idea of the decomposition method to its extreme and optimizing a minimal subset of just two points at each iteration.

Sequential minimal optimization (SMO) is an algorithm for solving the quadratic programming (QP) problem that arises during the training of support-vector machines (SVM).

In this article, we will consider a linear classifier for a binary classification problem with labels y (y ϵ [-1,1]) and features x. A SVM will compute a linear classifier (or a line) of the form: WT x + b = y

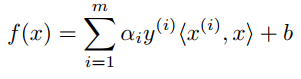

With f(x), we can predict y = 1 if f(x) ≥ 0 and y = -1 if f(x) < 0. And, without getting into too many theoretical details, this f(x) can be expressed by solving the dual problem as :

where αi (alpha i) is a Lagrange multiplier for solution and <x(i),x> called inner product of x(i) and x. The simplified SMO algorithm takes two α parameters, αi and αj, and optimizes them. To do this, we iterate over all αi, i = 1, . . . m.

The power of this technique resides in the fact that the optimization problem for two data points admits an analytical solution, eliminating the need to use an iterative quadratic programming optimizer as part of the algorithm.

At each step SMO chooses two elements αi and αj to jointly optimize, find the optimal values for those two parameters given that all the others are fixed, and updates the α vector accordingly. The choice of the two points is determined by a heuristic, while the optimization of the two multipliers is performed analytically. Despite needing more iterations to converge, each iteration uses so few operations that the algorithm exhibits an overall speed-up of some orders of magnitude.

Further, SMO was such an important development for SVMs mainly because of the limited use of computational resources required for the optimization. With SMO, we do not directly perform any matrix operations, and hence we do not need to store the kernel matrix in memory. This allows the SMO to run with limited memory, which is very useful for large data sets. If you are interested to know know more about SMO, here is a good resource that covers the theory a bit deeper.

fit functionNow, let’s get on with our fit function.

def fit(self, dataset):

self.dataset = dataset

# Magnitude of W is the key, list of W and b is the value

options = {}

First, we set the incoming data set as the data on which train the algorithms on. We also have the options variable initialized as an empty dictionary. The options variable will have the magnitude of W (||W||) as the key as a a list of W and b as the value.

For our choice of the two points we need determine it by a heuristic (it can also be random). For our case, we will use the heuristic as the min and max feature values, so we can start at the out-most ranges and converge inward.

all_feature_values = []

for yi, attrs in self.dataset.items():

for attr in attrs:

for f in attr:

all_feature_values.append(f)

self.max_attr = max(data)

self.min_attr = min(data)

del all_feature_values

We can get rid of all_feature_values to save up some sweet memory space. Next, we need to think about the step sizes we are going to use whilst performing the optimization. We are essentially starting at the out-most ranges, so initially our steps sizes can to be big. This makes the first pass optimization faster and having small step sizes at the initial pass does not improve the optimization values. We sequentially go through smaller and smaller step sizes as we find the local minima for each pass. So, for each pass, we have smaller step sizes and at the same time, smaller range of values to search for in our quest for finding optimal values. With this optimization, we are approximating the optimal values for W.

For this case, we are going to have three step sizes. Each orders of magnitude smaller than the previous one. We also have to initialize the initial value (latest_optimum) of our vector W. For simplicity, we will just have one unique value in out vector ie. we will repeat the same value in all the elements of the vector. While, this is unarguably a very sub-optimal way of going about things, the SVM with this limitation still performs well - which is a testament to how good the algorithm is. We will set the default value of our latest_optimum as positive infinity, since we want any value derived from the first optimization step will replace it.

step_size = [self.max_attr * 0.1,self.max_attr * 0.01,self.max_attr * 0.005]

latest_optimum = float(inf)

Now that we have basic setup for finding W, let’s focus on b. We will define the range and the multiple for b. We can set it to35 (which is very expensive anyway, since we are more sensitive to the value of W than we are of b). The b_range will be out extended range from the min and max heuristic that we have chosen. b_multiple is essentially our step size for finding b.

b_range = 3

b_multiple = 5

We then define our 4 dimensional transform list (since we have 4 feature attributes), which will have the values of [1, 1, 1, 1], [1, 1, 1, -1], [1, 1,-1, 1], [1, 1,-1,-1], [1 ,-1, 1, 1], [1 ,-1, -1, 1], [1 ,-1, 1, -1], [1 ,-1, -1, -1], [-1, 1, 1, 1], [-1, 1, 1, -1], [-1, 1, -1, 1], [-1, 1, -1, -1], [-1,-1, 1, 1], [-1,-1, 1, -1], [-1,-1, -1, 1], [-1,-1, -1, -1]. Having this as a list will make it easier to perform the transformations.

trans = [[1, 1, 1, 1], [1, 1, 1, -1], [1, 1,-1, 1], [1, 1,-1,-1], [1 ,-1, 1, 1], [1 ,-1, -1, 1], [1 ,-1, 1, -1], [1 ,-1, -1, -1], [-1, 1, 1, 1], [-1, 1, 1, -1], [-1, 1, -1, 1], [-1, 1, -1, -1], [-1,-1, 1, 1], [-1,-1, 1, -1], [-1,-1, -1, 1], [-1,-1, -1, -1]]

That concludes the initial set up of algorithm. Next, we dive right into the optimization steps. We first initialize the W vector as a list of latest_optimum values. We also need a flag to break out of the optimization, once we feel that the values cannot be optimized further. The fact we are essentially solving for a convex optimization problem gives us the luxury of knowing when the optimization has been completed.

for step in step_size:

W = np.array([latest_optimum,latest_optimum])

optimization_flag = false

We can now jump right into the loop. We keeping optimizing until we know that we have hit the limit (ie. the optimization_flag is true). We can start the inner loop with the range of values that we are considering out optimal b to be in. This would be the range of all values between the maximum attribute value and the negative of that value. Within the inner loop, we will perform WT, which as mentioned before, is just multiplying the defined W will all the elements of the trans array. The inner loop will look like:

while not optimization_flag:

for b in np.arange(-1*(self.max_attr* b_range ), self.max_attr * b_range, step * b_multiple):

for transformation in trans:

W_t = W * transformation

This is where we jump into the computationally expensive part. We go through the entire data set and perform out calculations to make sure it fits as well as possible. For every single data point in our training data, we check for the equation yi(WT.xi + b) >= 1, even if there is a single data point which does not conform to the above equation, we no longer continue. We can have a flag (found) to keep track of whether all of the data points conform to the aforementioned equation. If we happen to find a the values where we are able to satisfy the equation, we will then update our options dictionary. We calculate the magnitude of W using numpy’s linalg.norm. At this point, our inner loop looks like this:

for step in step_size:

W = np.array([latest_optimum,latest_optimum, latest_optimum, latest_optimum])

optimization_flag = False

while not optimization_flag:

for b in np.arange(-1*(self.max_attr * b_range ), self.max_attr * b_range, step * b_multiple):

for transformation in trans:

W_t = W * transformation

found = True

for yi, attributes in self.dataset.items():

for xi in attributes:

if not (yi * (np.dot(xi, W_t) +b )) >= 1:

found = False

break

if found:

options[np.linalg.norm(W_t)] = [W_t, b]

Now, let us define our optimized case. This is where the myriad of assumptions we have make come into play. To summerize, we assumed that W is gonna be in the form of W=[C,C] for simplicity, and then we starts with C at a value of infinity. Then we check all 4 possible transformation of W ([C,C] [C,-C] [-C,C] [-C,-C]) and keep only the viable ones. The viable ones are the ones that satisfy the condition yi(xi.w+b) >= 1. Then we lower the value of C by the step and repeat the same process. So we know that we have checked all the steps when the value of C goes below 0. For optimization flag to be true, we just need to check if w[0] is less than 0. This is because not every step i better than the previous, or more optimized. We only care about the final state. Since we are checking all 4 symmetrical cases for W for various values of C, there is no point in checking negative values since by having negative values for C would result in double checking cases we have already checked. So we can safely stop the optimization pass once we have the value of W[0] (or W[1] since they are the same value) goes below zero.

In case, we have not reached the local minima, we just move on to the next step.

if W[0]<0:

optimization_flag = True

print("Optimized by a step: ", step)

else:

W = np.array(list(map(lambda w: w-step, W)))

After all of loops within the pass is done, we have to set the values for W and b for them to be used by the predict function. We choose the lowest magnitude value from the options as the most optimal one. We then update the latest_optimum for the next pass.

norms = min([n for n in options])

self.W = options[norms][0]

self.b = options[norms][1]

latest_optimum = options[norms][0][0] + step*2

So, in the end, our fit function will look like:

def fit(self, dataset):

self.dataset = dataset

# Magnitude of W is the key, list of W and b is the value

options = {}

all_feature_values = []

for yi, attrs in self.dataset.items():

for attr in attrs:

for f in attr:

all_feature_values.append(f)

self.max_attr = max(all_feature_values)

self.min_attr = min(all_feature_values)

del all_feature_values

step_size = [self.max_attr * 0.1,self.max_attr * 0.01,self.max_attr * 0.005]

latest_optimum = float(inf)

b_range = 3

b_multiple = 5

trans = [[1, 1, 1, 1], [1, 1, 1, -1], [1, 1,-1, 1], [1, 1,-1,-1], [1 ,-1, 1, 1], [1 ,-1, -1, 1], [1 ,-1, 1, -1], [1 ,-1, -1, -1], [-1, 1, 1, 1], [-1, 1, 1, -1], [-1, 1, -1, 1], [-1, 1, -1, -1], [-1,-1, 1, 1], [-1,-1, 1, -1], [-1,-1, -1, 1], [-1,-1, -1, -1]]

for step in step_size:

W = np.array([latest_optimum,latest_optimum])

optimization_flag = False

for step in step_size:

W = np.array([latest_optimum,latest_optimum, latest_optimum, latest_optimum])

optimization_flag = False

while not optimization_flag:

for b in np.arange(-1*(self.max_attr* b_range ), self.max_attr * b_range, step * b_multiple):

for transformation in trans:

W_t = W * transformation

found = True

for yi, attributes in self.dataset.items():

for xi in attributes:

if not (yi * (np.dot(xi, W_t) +b )) >= 1:

found = False

break

if found:

options[np.linalg.norm(W_t)] = [W_t, b]

if W[0]<0:

optimization_flag = True

else:

W = np.array(list(map(lambda w: w-step, W)))

norms = min([n for n in options])

self.W = options[norms][0]

self.b = options[norms][1]

latest_optimum = options[norms][0][0] + step*2

predict function:Now that we have the fit function implemented, the predict is much easier to implement. Using the optimal separating hyperplane we find in the fit function, we can predict the class of new incoming data points.

As mentioned above, we have to solve for y in the equation: WT x + b = y. y is our class. We have the values of x provided in the attrs param in the function. W and b are already calculated in the fit function. So all we need to do in the predict function is to just substitute the values of W, x and b, then we will have our classification (y).

Breaking the above equation down:

WT x = W.x (dot product). To perform the dot product we can use numpy’s handy dot function. Before that, we would have to convert our attrs array into numpy array, which can be done by using the array function. The + b part of the equation is a simple addition, so it is very straight forward. So, the python implementation of the equation will look like:

(np.dot(np.array(attrs), self.W) + self.b)

By implementing the above, we will have something like this:

import numpy as np

def predict(self, attrs):

#sign of the X(i).W + b defines the class

classification = np.sign(np.dot(np.array(attrs), self.W) + self.b)

return classification

Now that we have the predict function implemented, Now is the time to check the accuracy of our algorithm. As mentioned early in the post, we will be using cross validation for the same. We will take the test_set, for which we already know the classes, and we shall use our predict function to predict the classes using our model.

For the cross validation, we can create a test function on our CustomSVM class:

def test(self, test_set):

self.accurate_predictions, self.total_predictions = 0, 0

for group in test_set:

for data in test_set[group]:

predicted_class = self.predict(data)

if predicted_class == group:

self.accurate_predictions += 1

self.total_predictions += 1

self.accuracy = 100*(self.accurate_predictions/self.total_predictions)

print("\nAcurracy :", str(self.accuracy) + "%")

For our iris dataset, we can run the cross validation: svm = CustomSVM()

svm.fit(dataset = training_set)

svm.test(test_set)

Which has the output:

Acurracy : 100.0%

Although, a 100% accuracy is usually too good to be true and in fact is generally detrimental due to over fitting; in our case, for the simple, easily separable classes of the data set - this makes sense.

That’s it for now; if you have any comments, please leave them below.